New heat sees Down Under wine cops permit black snake dilution to 13.5%

by PHILIP WHITE

It says a lot about human love of intoxication, the arcane layers of law, lure and lore that we wrap around very basic drugs like alcohol.

Like in winemaking, we've long made it illegal to add water. This law was regularly, perhaps habitually, broken by cheats attempting to increase the volume of their product cheaply and by those more responsible makers who wanted their wine to be a more elegant, less gloopy, more drinkable affair

In Australia, the sunshine's often a touch too loud: it's generally very easy to get grapes ripe. Very ripe: until this recent Global Warming, our grapes easily guaranteed wines much stronger than the cold Old World vignobles. Now, they're having the same problems.

Wines have become so strong, in fact, that they're often so loaded with obvious, overwhelming alcohol - in the form of ethanol - they're of little gastronomic advantage. Which is dumb when you consider the great sales line of the vendors has always revolved around their powerful intoxicant being a compulsory magnifier of the delights of the gourmand table.

While the vendors avoided acknowledging that their product was indeed dangerous, the dry wowser interferists insisted it was, while governments pretended to agree with both sides so they could gluttonise themselves to a kind of intoxication on the taxes they could raise from our love of the glug.

The alcohol levels of most of the bottled wine I drank in the 'seventies and well into the 'eighties were, in today's standards, modest: 13.5 per cent was commonplace; 12.5 never to be snorted at. These were the types of alcohol levels Australian wines shared with the grand, impossibly expensive wonders of Bordeaux and Burgundy, where sunshine was often a bit thin on the ground.

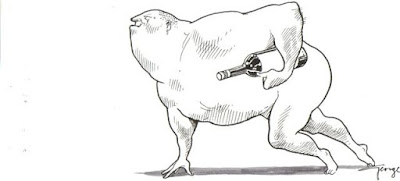

How did we achieve such levels? Either you picked early or you added water. The old "Black Snake" - the water hose - was an essential winemaking tool for more than wash-down. As modern, mindless over-irrigation became the norm, some alcohols stayed down because the little berries were so prolific and tight with water they could never properly ripen. There grew a certain downward spiral as we learned to move great amounts of water out of its natural channels and into vines: the location of most of those arid inland vineyards meant the wine would not be of the quality required to charge a proper price of the cognoscenti.

The next route to viability lay in tipping more water on the vineyard in pursuit of higher yields, and more wine, whatever the quality, which further lowered the product's value.

Many things influence alcoholic strength. Like rain: the Hunter Valley, for example, often can't pick at ideal ripeness because sub-tropical rains turn the ground to mud, limiting human pickers' access to the crop and ensuring big harvesting machines sink to their axles. If it rains too much the sugars - and alcohols - plunge; if it rains more modestly, ripening continues, often too quickly, but nobody can get in the vineyards.

In regions where the vineyards are more garden-like, and less industrial, the dependence on human pickers is greater, so the timing of harvest is often determined by the availability of labour. Get a heatwave without a corresponding influx of workers and you have to wait til they arrive, by which time your wine could have gone from 13.5 alcohols to 17 or more.

Same with harvesting machines: these are very, very expensive and in limited numbers. If things go through the roof, you have to put your vintage in the harvester queue. Stuff gets too ripe. If you have water, you can add it to your harvest via the vine roots, but it's illegal to add in the winery.

All this went nuts with the advent of a single US critic, Robert Parker Jr. His personal taste favoured huge alcoholic jam bombs. His astonishingly influential newsletter made such gloop popular, first amongst the emergent sommelier class, then aspirant north American foodies, and then even further afield: it was almost as if the USA, a country more known for Coke and fat than cuisine nouvelle, knew more about wine than Paris.

Australia follows Amurkha: up went our alcohols with the perfect Parker points and our fast food, fat, sugar and starch intake. Up went the national obesity. We trained an entire generation of winemakers to regard wines of 15 or more per cent as the norm.

Internationally, Parker's influence, fortunately for the modest epicure, has waned dramatically. But in Australia, the habit lingers, partly because many people love intoxication and have become accustomed to high alcohol wine. This, however, is assisted by the simple fact: it's a lot easier to grow and make highly alcoholic gloop than wines of balance and finesse.

One of the smartest ways toward reversing this trend is to first acknowledge its existence. This has taken twenty years. Next, we should work together to change it, which will be tricky in this new heat. How do we do that? In an unusually bright move, the authorities have changed the Food Standards Code

"Water may only be added to wine, sparkling wine and fortified wine to facilitate fermentation if the water is added to dilute the high sugar grape must prior to fermentation and does not dilute the must below 13.5 degrees Baumé."

University of Adelaide PhD candidate Olaf Schelezki reports that in his search to discover whether such addition might detrimentally effect the colour, tannins, volatiles or sensory aspects of wine, he had an immediate stroke of good luck: the trial vineyard he'd selected to test, in McLaren Vale, was hit by the heatwave of 2015. This blast of concentrated summer "saw the potential alcohol in the Cabernet sauvignon vineyard increase by nearly three per cent in barely three days," Olaf said, producing "a control wine coming it at 18 per cent alcohol and badly needing some attention.

"It was a classic example of the compressed vintages that winemakers are facing around the world: Unwanted heat at a sensitive time of the year," he explained upon the publication of his paper.

Olaf (above) tried two common treatments. He tried adding up to 30 per cent water to the over-sweet juice, and then another batch with 40 per cent of early-harvest green wine of less than 5 per cent alcohol. In both cases, he was surprised at how minor, if any, were the resultant detriments to the finished wine's character and flavour.

Not that it started out with much glamour: "It was a very overripe crop," he said, "very shrivelled fruit with almost port wine aromas and dried fruit, and these characters prevailed despite lowering the alcohol content ... It was not a great wine and the process did not change that. In this case it would have been better to avoid the problem and harvest earlier."

In the more comfortable 2016 vintage his crop came in at a potential 15.5 per cent alcohol: "one that might be open to stylistic tweaking but didn’t need drastic attention."

The wine with the added water was better. His preliminary 2017 results show that adding sufficient water to the ferment to drop one per cent alcohol had little detrimental influence, leading to the conclusion that "adding water is really not the big deal that some people have been perceiving it as, and is particularly benign in comparison to some other approaches to lowering wine alcohol content."

Halliebloodylooyah!

No comments:

Post a Comment