Orson Welles as Sir John Falstaff and Jeanne Moreau in Chimes at Midnight 1966

Big gastronomic risk, the Shiraz-whisky cocktail, so why would Jacob's Creek try it in the barrel?

by PHILIP WHITE

A drunken professor of

English literature once visited my apartment in the company of the Falstaffian John 'Lord'

Twining, who seemed considerably drunker but nevertheless supported a tiny

lass, a ballet dancer who besotted him and on this occasion, outsotted him too.

After an initial surge, she rested quietly beneath the dining table until morning.

I offered the gentlemen

refreshment from the assorted bottles open there before them. They chose to

drink Shiraz with Lagavulin 16 Years Old Single Malt Whisky, about

half-and-half. They insisted on whisky glasses, which was anthropologically

fascinating. And they tried various types of Shiraz in their Lagavulin.

We discussed the flavour

of their drinks, English literature and particle physics until I dribbled the

professor downstairs into an unwitting cab and climbed back to my attic in time

to see Lord Twining mistake the candle for his glass. Perhaps guided by its

friendly light, he lifted that flaming pot to drink it, setting fire to his

full white beard.

Through his grimy

spectacles, his eyes looked puzzled more than alarmed as he gazed across the

conflagration.

I could smell the beard in

the morning. It was in the tea towel. But one single stink rose ghoulish above

even the cindered whiskers: the smell of the dregs of those bloody cocktails.

That evening flickered

across the old eyelid cinema when I read this week that Pernod and Ricard, those

ancient absinthe and pastis families of France, were using their Jacobs Creek

brand to trial red wines aged in used whisky barrels.

Writing from the Ivy

League corner of the USA, Wine Press blogger Ken Ross reported this reversal of

the travesty I saw committed at my very table. Ross thought the Jacobs Creek

Double Barrel Non-vintage Shiraz aged for a while in used scotch whisky barrels

had a "richer, fuller, slightly long aftertaste," but he preferred

the Double Barrel Cabernet which had been finished in Irish whiskey

barrels.

"As a longtime fan of

whiskey and bourbon, I was hoping for slightly more whiskey flavors in both

wines," Ross concluded.

Let's get this into focus.

When I ran into malt whisky in the 'seventies it was mostly made in old sherry

barrels. Given the Scots' appreciation of a sporrun full of coinage, paying for

new oak barrels to mature their whisky was not a consideration. Scotland bought

barrels nobody else wanted.

Until all the traumatised

post-war English had drunk themselves to quiet Anglican deaths on sherry, that

Jerez business boomed and used barrels were dirt cheap, just across the Channel.

The powerful cask-strength

Scotch spirit, basically barley vodka distilled to 60-70 per cent alcohol in

copper pot stills, would tear into the insides of those barrels, sucking

caramel and a rainbow of flavours of sugar, old wine and sap from the oak into

the liquor, flavouring and colouring it.

As the sherry drinkers

died and the barrels ran out, Scotland leant increasingly on the north American

whiskey makers for used barrels. For Bourbon, Kentucky whiskey, rye and

whatnot, the general rule is that the spirit must be aged for three years

minimum in American oak barrels which must then be discarded. To protect the

character and quality of the whiskey, only new barrels can be used.

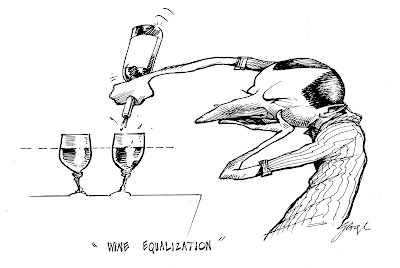

Barossa cooper's hand by DRAGAN

This suits the Scots. They

snap 'em up. Get another dozen years out of them. But what nobody ever

mentioned was the fact that just quietly, the distilleries of Scotland

gradually changed the flavour of the whisky we drank, from sherry-flavoured

barley spirit to Bourbon-flavoured, often tinted and sweetened with caramel.

By the mid-eighties

visiting Scotsmen had begun to talk about trying other types of barrel. Brian

Morrisson, of Bowmore Distillery on Islay tested us on the infamous Black

Bowmore, a midnight sin of a drink made by ageing the spirit in oloroso sherry

barrels instead of those used for dry pale sherries. That black, sticky dessert

sherry sure made a a deadly incendiary gadget of the barrel-strength malt. But

it took another decade before we saw official bottles on the shelves, at some

ridiculous cost. Unsure of its potential in the traditional Old World malt

markets, Morrison had been selling it to the Australian Gillies' Club, at full

strength, by the barrel, for home bottling.

Then David Grant, the

Highland distiller, came to test me on some trial batches of malt whisky aged

for various durations in brand new American and French oak. He was so delighted

by my curiosity that he bothered to sort the excise and sent me further cask-strength

samples: full litre bottles, thankyou Sir.

This was truly

enlightening. For the first time I realised how closely the raw pot-stilled

malted barley spirit resembled slightly smoky vodka, while the pure grain

spirit, unmalted, was very good vodka indeed. After a few years in the new

barrels it took on a distinct citrus aroma and flavour, a little like curaçao.

I never saw this on the market; I suspect it was hidden away in what became

known as The Balvenie, another expensive luxury malt in a very posh bottle.

Barossa coopers' hands at Langmeil ... photo by DRAGAN

As the years wound by we

saw numerous whisky distillers trial whatever used barrels they could get their

hands on: the cellars of Sauternes, Burgundy and even Bordeaux were leant on

for old wood. There were pink whiskies, burnished botrytis-tinged whiskies: all

sorts, sold at a premium as special numbered bins or batches. This desperate

fad seems to be subsiding, at least as a marketing tool. Overall, the punter,

unimpressed, will not continue to pay.

Especially in China.

Meanwhile, the huge engine

of the Scotch business gurgled on, using whatever cheap timber it could get. For

the time.

Like its rival

transnationals at the huge end of town, Pernod Ricard owns many scotch

distilleries and brands, including the distinguished Chivas Brothers.

So it was a wry smile I

wore reading the news of the continuing double-digit decline in Chivas

Brothers' whisky sales in China. Pernod Ricard's rival Diageo, maker of Johnny

Walker, also reports a 42 per cent slump there.

This is big trouble for

these monoliths.

Being deeply concerned

with their shareholders' interests, I suspect these giant spurruts companies

will be scrambling to work out what to do with all those old whisky barrels

they've accumulated during the boom. There'll be cooperage accountants

beavering away in the back rooms, pestering winemakers to make use of them anyway

they can.

Especially at Pernod

Ricard Australia, whose recent numbers aren't too hot.

This is all very

mischievous, but I can't help wondering whether that wild moist night in my

apartment was a spooky voodoo warning of highly unlikely flavours to come.

The

ghosts of those departed guests hover here in the light of the burning beard, reminding

me that whisky, Shiraz and blazing whiskers do not go very well together.

But all is not lost. I

believe the best malt whiskies on Earth are being made in Japan and Tasmania.

For that top-shelf tipple you keep secret in the back corner of your desk, go

Yamazaki or Hellyer's Road 10 Year Old Tasmanian single malt.

For inexpensive blended

Scotch, Teacher's Highland Cream will do the trick.

Add Shiraz to your liking.

photo©Philip

White