Post Modern Wine Fire ... Aussie Vineyards Burning ... Bad Billboard For Wine Biz

by PHILIP WHITE - A VERSION OF THIS APPEARED IN THE INDEPENDENT WEEKLY

Now that the bulldozers have started, the Australian wine business faces one of the most awkward marketing problems it could encounter.

Vineyards are like vast billboards for wine, and for winemaking communities.

You don’t need a sign saying “Australian Wine Industry” in the middle of an horizon-to horizon Nuremberg rally of vinous monoculture. You’re in the middle of a much bigger advertisement for wine than any planning regulation would ever permit a signwriter to erect.

This was recognised in the eighties, when the Vine Pull Scheme was stopped, more on the grounds of the ruination of heritage and civic amenity, than anything much to do with the modern wine business.

Vineyards are dreadfully honest advertising, too. Vignerons have little idea that the droll repetition of the grapeyard can be a pretty good indicator of what flavours the bypasser should expect. By their fruit ye shall know them.

So now that the tourist will be driving through terrain scarred by bulldozers, inhaling the wafting smoke from mighty piles of dead vines, does that person feel like pulling in for a case of premium? Do they recall that just months ago the proprietors were telling us this was a great thing, this vineyard, and its fruit?

Vineyards fried to virtual extinction by drought and sunshine are one thing; vineyards bulldozed and put to the torch are another.

Vine-pulls are bad for the captains of industry. Anybody who encouraged such plantings in order to lower prices – look like greedy, unscrupulous cretins. But they’ll move on: swap boards; swap industries. They’re just as likely to be on the board of the Scrubbed Pine Red Setter Kennel Company tomorrow.

When the vineyards burn, the biggest damage is dealt more innocent folks. The humiliation instilled by a large-scale vine-pull is deadly to those who must pull. I can’t forget the old men weeping openly in pubs in the Barossa in the mid-eighties, after they’d pulled their grandfathers’ gardens out. Pulling the vines was like pulling the teeth of the entire community, without anæsthetic. Families fall to bits. Suicides occur.

When the vineyards burn, the biggest damage is dealt more innocent folks. The humiliation instilled by a large-scale vine-pull is deadly to those who must pull. I can’t forget the old men weeping openly in pubs in the Barossa in the mid-eighties, after they’d pulled their grandfathers’ gardens out. Pulling the vines was like pulling the teeth of the entire community, without anæsthetic. Families fall to bits. Suicides occur.The wandering wino may miss this cruel undercurrent, and drive about bathed in the sanctimonious light of the opportunist about to make a killing, buying wine at bargain prices when the international market is overflowing.

But what does gross oversupply really mean to the wine lover?

First, it means quality drops. When the refineries are competing to control the bargain bins of Europe, they must make wine at cheaper and cheaper budgets. Corners are cut. Sawdust replaces barrels. Shovelled acid and tannin replace what trimmed vineyard budgets failed to achieve naturally. The “make” budget shrinks; the “promo and packaging” budget swells.

Second, it means quality drops. When growers suddenly find themselves without a grape purchaser, they’re faced by a cruel choice. They can spend money they don’t have making the wine themselves, or spend money they don’t have hiring a bulldozer to rip the vineyard to make way for almonds (if only) or car yards. Most try to make a wine. Others let the grapes hang, and let the vineyard fall into disrepair, hoping Mary MacKillop or somebody will send a buyer along next year.

(Unlikely. Since her sainthood, Mary has made it essential that a freeway bypasses Penola, which would slash a great swathe of Coonawarra vineyard asunder.)

Whether in a wheelie bin or a contract refinery, 2010 has seen a stupendous amount of wine made on spec by people who can’t afford to do it properly – precisely the sort of wine directly responsible for the collapse of international respect for Australian wine in the first place.

Hoping that some cleanskin dealer will emerge at the last minute with the money to pay for bottling, many Australian working families have turned their 2010 crop into bulk plonk. They’ve done it in mate’s sheds, or pulled the cash sock out and paid a contract refinery to convert their grapes to alcohol, which is at least semi-stable, and may last. As long as they can afford the tank rental.

So, within the next couple of years, the lake of unsold wine in Australia will be joined by a tsunami of poorly made plonk, sold at increasingly diminishing returns out of mendicant desperation.

Which, to summarise, means that, third, quality drops.

If they are lucky, the mongers of this plonk might find some nefarious Flash Harry to sell it in China. If it’s white, forget it. If it’s red, sugar it up, fizz it up, put a golden dragon on it and flog it as an Aussie heritage item that will heal your teeth.

But mark my words, within a few years, we will be buying our teeth etching fluid from China. It will be called Premium Wine Of China, and they’ll put kangaroo dot paintings on it, broken fish plates, Cohiba cigar labeling; whatever we want. It may well be better than what we’ve sold them.

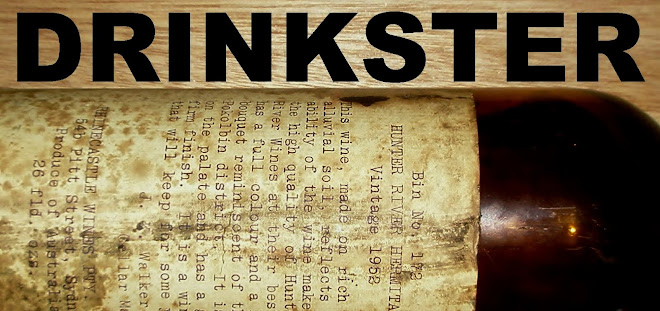

The wines I recommend on this page are not like these. As a buyer, you have the best chance yet of choosing which bits of the business you’d like to see survive.

BETWEEN SCORCHING DESERT AND DERANGED GUNMEN, VINEYARDS ARE BEING PUT TO THE TORCH

BETWEEN SCORCHING DESERT AND DERANGED GUNMEN, VINEYARDS ARE BEING PUT TO THE TORCHCynicism Aside, This Crap Is No Surprise ... Any Fool Could See It Coming

From the archive: January 2006. This is the sort of writing that led to Melvin Mansell, editor of Rupert’s Advertiser, firing me after twenty years of wine columns.

“The Vine Pull words excite people”, says Paul Clancy, chairman of the new Wine Grape Growers Australia. I’d asked about current rumours of another such episode, when government pays hopeless grapegrowers to uproot vines and leave the business. This last occurred in the mid-eighties.

“There IS talk of a Vine Retirement Scheme” Clancy says. “Just different words. The wine industry doesn’t like too much government intervention, but we’ve got growers going to the wall right across Australia, and a fair slab of the blame lies with Canberra, so we’re having a meeting of appropriate parties there next month. Everything’s on the table.”

Sinister things happen in a big wine flood. Hardest bit to swallow is that some wine might get cheaper, but it never improves in quality. The refineries are under immense pressure to cut their winemaking budgets to compete with speculative bottom-feeders. Things fall apart. Lakes of heartless swill flood Australia’s tankfarms. Drinking a bargain? Toast the poor grower who went broke. Poor fella my country.

And on it goes. Apart from the abundance of dubious cleanskins and bladder packs, and their massive environment and public health costs, the biggest change to hit the sensitive wino during a Vine Pull Scheme is social. Many grand old families were gutted during the last effort. Walk into any Barossa bar and it was in your face: good people grievously distressed about uprooting their great-grandfather’s beloved vines.

Tourist attraction? Men with blank teary faces gazing into too many schooners of stout? You’d flee outside, to find the whole valley shrouded in wafts of smoke from the smouldering windrows [SUBS: WINDROWS NOT WINDOWS] of ancient vines. It went on and on. The big companies wouldn’t pay enough; so the government paid. To destroy the gardens. Ein prosit.

Whatever it’s called, the next uprooting will be more widespread. With any luck, and with Clancy’s immense capital of hindsight, this time we’ll pay to remove stuff we won’t drink. If nobody wants to buy it, if the growers can’t afford to have it made, then they can’t afford to pick it, much less cough up for the conversion to better varieties. Or pay the bulldozers.

Clancy contemplates government assistance paying for the clearance of failed vineyards, to be repaid by the industry through a small levy on the long-term professional viticulturers who stay in the business and survive. “It’s in their interest”, he says.

Politicians must cease their blithe effervescence over the wine business. A responsible planning and establishment cycle for a serious new winery development is at least twice the life of a government, three or four of them if you were a man of category, like David Wynn. But, just like the big refineries encourage gluts to keep costs down for their shareholders, politicians see the wine business as some sort of Instant Lite: a cute, popular, and safe novelty El Dorado. Forget the water issues: think of the export!

“The tax regimes attracted all the wrong people” Clancy bemoans. “In it for the wrong reasons. Real men of the land in all regions find their livelihoods crushed by a planting boom talked up by big wineries and ignited by tax minimisers who have no interest at all in viticulture or the economic and social impacts on the country. It’s Australian against Australian. Well done those men.

”There are rice farmers up the river in New South Wales, for example, putting in thousand acre vineyards simply because they can. They’ve got cheap water and flat land.

“Then, a lot of others have planted in the wrong bloody places. Like the Hills. The only growth in export sales is below four pounds ninety-nine a bottle in the UK and you can’t possibly grow cool climate grapes at that price. The cool climate regions are now producing forty per cent of our grape supply but generating only sixteen per cent of demand.”

In case your bargain wine hasn’t curdled, consider: you may not have invested in these failures, but you pay three times anyway. When government spends your money paying tax-avoiding speculators to uproot and piss off, it’s not the end of the story. Somebody has to make up for the tax not paid. And then we pay again for the rehabilitation of the land. Not to spend too much time reflecting on all that wasted water. The wine industry hasn’t quite grasped that water is a vital gastronomic item.

Maybe it’s time to kick a wine refinery into reality with some king-hell distillation. Make petrol. Get the McGuigan Simeon mob, you know, Nick Greiner, Perry Gunner and Brian McGuigan, on the job. They blame high petrol prices for the slump of their bottled wine sales. So sort out a few harbours of cheap water with the Member for Schubert and the lass up the river, and plant more. Market it varietally at the bowsers. Mine goes better on cabernet, mate. C’mon Kero, you won’t win by tilting at trams. Go positive! Go Petrol! The punters’ll love it. We could be self-sufficient!

NOTES FROM MY INTERVIEW WITH CLANCY INCLUDE THESE COMMENTS:

For what it’s worth, I have some rather unfinished ideas about removing vineyards at the taxpayers’ expense, even if that cost is eventually reimbursed by the industry.

A formula should be devised which includes the following:

1. Last in first out. Youngest plantings go first.

2. Prices of last crops. Most recent market prices should be included so lowest incomes are the first to go.

3. Water used to achieve that price. A ratio should be devised that sees those who have used water most inefficiently should be at the head of the queue for removal; i.e. growers who use more water to achieve lower income should go.

... and back to 1999: referring to the National Wine Centre ... the budgie syndrome:

Excerpt from my speech to planning students at the University of Adelaide, Wednesday 13th October, 1999. A slightly shorter version of this address was delivered to the Australian Institute of Urban Studies, S.A. Division, at Chesser Cellars, Friday 26th March, 1999.

So what started as a simple, profit-making service for visitors quickly became a State-funded wine museum, which quickly reverted to an office block for bureaucrats and mandarins, partly because nobody thought the word museum was much good in this modern age. On the committee I joined at Premier Brown's invitation, the first wine centre committee, the word museum was abandoned because nobody really knew what it meant.

None of those great brains had heard of Zeus, or Jupiter, the boss of the heavens, nor of his wife, the Goddess Mnemosyne, or Memory. They didn't realise the daughters of this couple, the cover girls of their day, were the official inspirers of all poetry and art. Cleo was the trigger of history, Thalia of comedy. Euterpe was the source of all music; Urania of astronomy, and so on. They were called the Muses, just like my much uglier lot's called the Whites. The Muses lived in the Museum.

No good, no good. It'll have to be the National Wine Centre. It'll have to be in the Botanic Park because:

1 The Gardens already attract 1.3 million visitors a year - more than any other government-owned property;

2 The East End is already a famous tourism and gastronomic precinct (The Universal Wine Bar's there), and

3 It's a nice place to have your offices.

They overlook the fact that the East End is rapidly becoming a violent drug-crazed mirror of the old Hindley Street, where a good deal of the working community are the enthusiastic users of a constant wave of powder drugs; and they don't realise that the very reason that 1.3 million people visit the Botanic Gardens each year is that there are no industrial headquarters, office blocks, car parks, conference centres, or monorails in sight.

Don't laugh - a monorail was seriously suggested, to siphon customers from Rundle Street across the Botanic Garden, which is a dry zone, to the Wine Centre. This was seen as a possible solution to the car parking problem in the Garden. Nobody listened to the traders' complaint about the loss of business in Rundle Street, because there's no real parking there, either. Anyway, show me a monorail and I'll show you a Premier who's just lost power.

The initial concept for a straightforward, self-funding facility for wine enthusiasts was sufficiently attractive to lure a horde of self-interested political amateurs and industry mandarins, whose clumsy and transparent manoeuvres in pursuit of taxpayers' funds and sacred inner city parkland, abuse not just the clarity of the first proposal, but snigger in the face of the uncommonly tasteful and discerning community of Adelaide.

After five years of squandered expense and volunteered energy, this centre is further from its origins than credibility extends.

The citizens of Adelaide now face the construction of an industrial headquarters in their extremely popular Botanic Garden. This $40 million-plus tax-payer-funded Xanadu will have little purpose beyond housing the bureaucrats who will be responsible for the next taxpayer-funded Vine-pull Scheme.

There has been no consultation with the neighbours, none with the community at large, nor anything vaguely resembling consultation with the wine industry proper. The old buildings wisely rejected by the wine industry will now house the unfairly misplaced botanic scientists whose perfectly suitable, unobtrusive buildings and laboratories will be demolished to make way for the imposing new wine industry headquarters.

Those who intend moving into this facility, like Wine and Brandy Corporation Manager, Sam Tolley, refer to it as their "new offices". Winemakers Federation of Australia Chairman, Brian Croser, admits privately that the centre, as imagined by him, does not "necessarily have to be in the Botanic Garden".

Those who intend moving into this facility, like Wine and Brandy Corporation Manager, Sam Tolley, refer to it as their "new offices". Winemakers Federation of Australia Chairman, Brian Croser, admits privately that the centre, as imagined by him, does not "necessarily have to be in the Botanic Garden".And driving force Ian Sutton, Chief Executive of the WFA, Wine Australia Pty. Ltd., Australian Wine Foundation and the Australian Wine and Brandy Producers' Association, says "My job's not to consult the wine industry -- my job is to represent the wine industry".

Now that Glenthorne Farm, a perfectly suitable alternative site for a self-funding centre has been found and purchased on the old CSIRO research site at the top of Flagstaff Hill, those who would raid the public purse, not to mention the Botanic Garden, have become more secretive and even more determined in their nefarious pursuit.

1 comment:

Hey Sr. Blanco, you're either loco or stupidly brave. Don't you think this windmaill's too big for your tilt?

Post a Comment